What even is robotics anyway?

It’s my first blog post! I’m going to use this as a testing ground for Jekyll’s markdown rendering.

Going into my undergraduate degree at UCSD, I knew I wanted to study robotics. However, when people asked, I wasn’t able to give a very clear description on what exactly the field is about. This is because the amount of domain knowledge that goes into building a robot is massive - no one person can specialize in all of it. This blog post is for anyone in a similar position as I was - here is an info dump on about what the field entails.

What is a robot?

A robot is any machine that is designed to accomplish a specific task without human intervention1. Some examples: * A roomba - vacuums your floor * A self driving car - drive someone from point A to point B * Boston Dynamic’s Spot - used for navigating areas where wheels aren’t very effective In the context of my current masters program and of academia in general, robotics focuses a lot on the algorithms that allow robots to process data and autonomously make decisions accordingly. Much of the innovation in robotics is currently being made in these areas, which I had no idea existed when I was younger.

Robots are Systems

Fundamentally, robots have many components that need to work together to get it to do the thing it was designed for. These include:

- The mechanical design of the robot - what will the robot use to accomplish the task

- The kinds of sensors a robot uses - how it will observe its environment

- The electronics that power the robot and allow it to process data

- The algorithms the robot follows - how data translates to an understanding of where the robot is in its task (sensing and estimation), and how understanding translates to the next action (control)

When I was younger I had the impression that I would be able to do all of these things - this is not true. Like many areas of engineering, robotics is an intensely collaborative field, where people with different specializations cooperate to build the best robot they possibly can. One can have some knowledge of all of these domains, but actually putting in the work for all of them in a single project is usually infeasible.

The Body (the part I’m less familiar with)

There’s a lot that could be added to this section that I’m nowhere near qualified enough to address, though for now, have an extremely high level overview.

Mechanics

The mechanical design of a robot is less concerned about aesthetics and more about a concept called degrees of freedom (DOF). This determines the range of motion the robot can have, and the flexibility with which the robot can achieve different positions.

Electronics

These are the components that control the physical actuators and keep the brains of the thing alive. Most of this is not necessarily specific to robotics, but it’s still a vital part of getting the robot to actually do something. Some people may also lump into here the processing unit that runs the program which does the decision-making. A possible choice for prototyping might be a small but full-featured computer like a Raspberry Pi or an NVIDIA Jetson, though to cut down on cost in the end, it may be worth the effort for some to move onto a more specialized embedded processor that doesn’t run a user-level operating system. Often times in robotics some guarantee of when tasks should finish is desired, so a real-time operating systems or RTOS may be desirable in those cases.

The Brains (the part I study)

Sensors

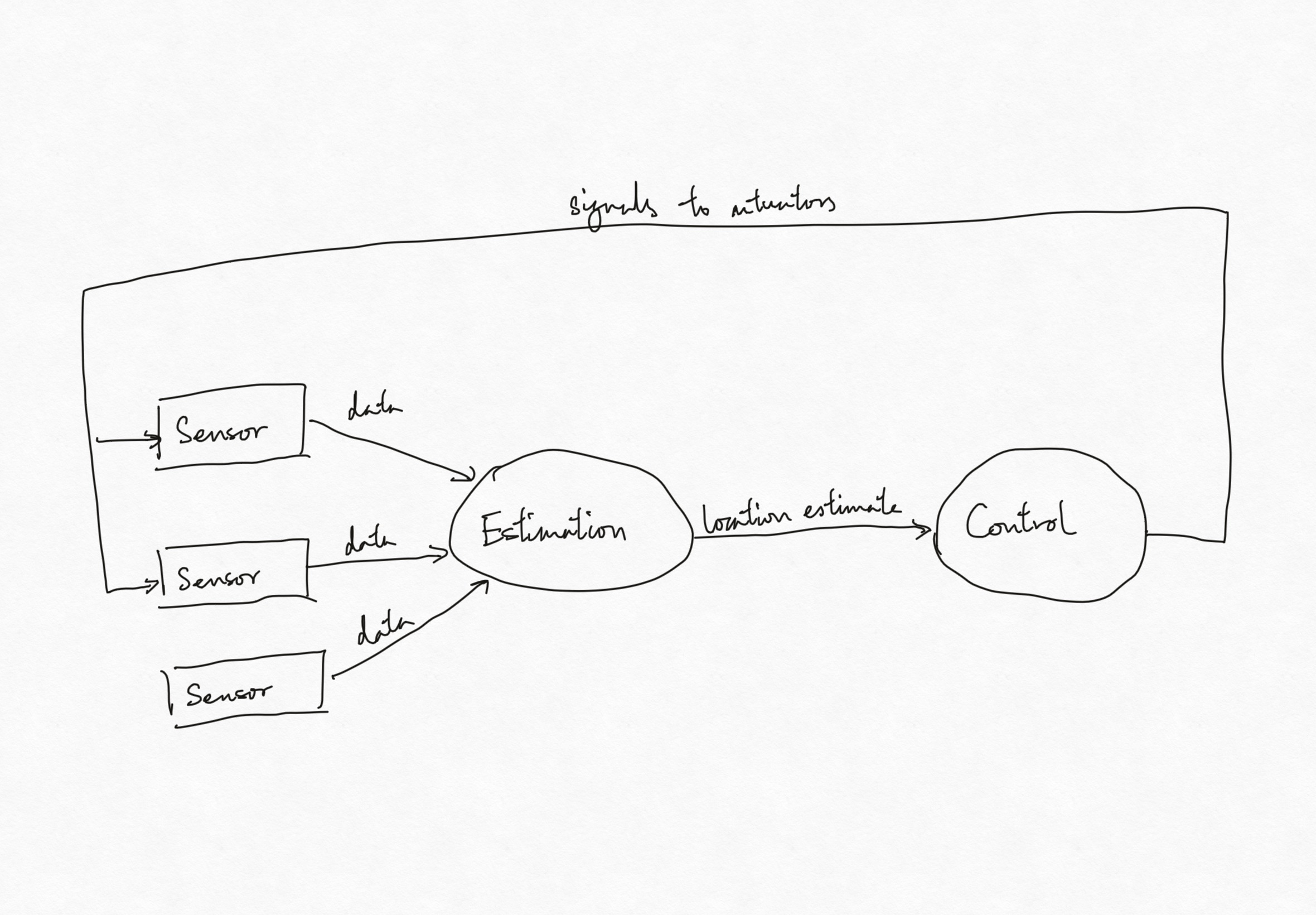

As a robot, making a decision involves getting some information from the outside world, using it to create some understanding of where it currently is in a task, and use that to determine the next action. Robots get data about the world using sensors. These are instruments that can measure something about the robot or its environment, and translate that to a signal that the onboard processor can read and interpret. A system diagram of this process might look like this:

There are many different types of sensors which I won’t describe here, but I personally like to divide them into two categories. These distinctions mostly matter for estimation, which I’ll outline in the next section.

Local sensors

These get information about the robot itself, like how fast it’s moving, how fast specific wheels are rotating, anything that would remain the same irrespective of the robot’s environment. Generally this comes from the robot’s inertial measurement unit, and rotary encoders on the wheels or joints.

Global sensors

These get information about where a robot is in relation to its environment. Examples include ultrasonic sensors, LIDAR, cameras, or GPS.

Estimation

Estimation is the process of understanding where the robot is in space. Not all robots necessarily do this, though if a robot needs to move through an environment, this is an important step to do so. The key phrase here is called simultaneous localization and mapping, or SLAM for short. Typically, SLAM is accomplished by using Bayesian statistics (called a Bayesian filter) to determine a new possible location by combining a prior guess of the robot’s current location with given readings of the robot’s environment. A mathematical model of both the robot’s motion (called the “motion model”) given its actuators and how observations of the environment will change given its motion (or the “observation model”) must be known beforehand.

An important thing to note here is that sensor readings will not give a 100% accurate estimate of where the robot is - this is why the motion model is expressed as a probability distribution rather than a discrete value. This means the resulting state estimate is also a probability distribution, but we generally make some assumptions that allow us to assume the mean of that distribution is the most likely configuration of the robot’s state.

Control

I like to divide control into two fields: how a robot decides its next step in “decision space”, and actually transitioning to that state in the real world.

Deciding What to Do

A common way to formulate the former problem is to express the robot’s state as a vector, and create a structure called a Markov Decision Process or MDP to mathematically describe the robot’s possible states and desirable goals. Methods to best solve these for different kinds of robots are being heavily studied in research.

Actually Doing It

To actually move from point A to point B, this is typically expressed by attempting to minimize the error in between where you are and where the next point is. There are multiple layers to this - there’s the overall difference between where the robot is and where it needs to be, and there are the configurations of the individual actuators on the robot that need to be adjusted to reach that state.

What this means for you

If you’re looking to study this field, chances are that no one program teaches all of these at once - at least within their core material. Learning all of this and understanding it at a deep level is a massive time investment, so don’t be discouraged if this seems overwhelming. People generally aren’t expected to know everything going in, so take some time to explore which of these domains hold the most interest for you, and go from there.

Footnotes

-

I only learned while writing this that there’s an ISO standard for the the definition of a robot, which focuses on being able to determine what to do based on sensory input as opposed to a list of instructions. Read ISO 8373:2021 if that sounds interesting. ↩